Richard Burton and the expedition to Harar

23/08/2021

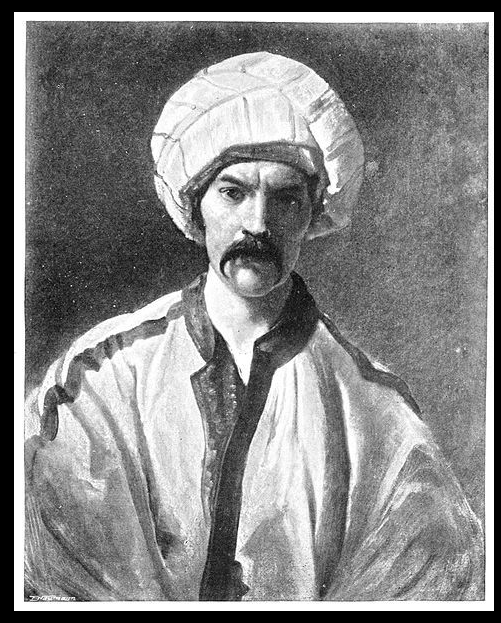

Richard Francis Burton (1821 - 1890), English explorer

Sir Richard Burton was an extraordinarily brave explorer, scholar and a genius for language and disguise. A year before this trip to Harar he became the first European to enter Mecca.

Don Pinnock

On an expedition several years after visiting Harar, John Speke discovered Lake Victoria and therefore the source of the Blue Nile. Burton, who was unwell at the time, was furious and called him a liar, ending their friendship. Burton would elope with his childhood sweetheart Isobel Arundell in 1861, write more than 40 books and translate from Arabic The Arabian Knights and the Kama Sutra from Sanskrit. It’s considered to be the first book of pornography in English and was promptly banned. He eventually received his knighthood. After the side-trip to Harar, Burton returned to Berbera on the coast where he joined Speke on another expedition that nearly cost them their lives. But that’s another story

***

There were really only two possible outcomes of the journey: death or fame. The first seemed to concern Richard Francis Burton not at all, the second most certainly did: he craved a knighthood.

His destination was Harar in eastern Ethiopia, a forbidden city that no European had ever seen. He’d been warned that it was a city which you might enter at your own will but leave only by that of another. He was told that the route he planned was “disturbed” and that smallpox was raging in Harar.

There was another problem: though Burton spoke almost flawless Arabic (he knew 25 languages and dialects) and was disguised as a Saudi merchant, his white skin made him seem Turkish. Ethiopians hated Turks. The signs were not auspicious.

In a letter to his friend, JG Lumsden, he set out his strategy of engagement with the “fanatical” Somalis through whom he would travel: “You must be on extreme terms, either an angel of light or a goblin damned. Walk up to your man, clasp his fist, pat his back, speak some unintelligible language, laugh a loud guffaw, sit by his side and begin pipes and coffee.”

His caravan left the town of Zeila on the Gulf of Aden on 27 November 1854. It consisted of five camels, 50 donkeys, three Somali attendants named Mammal, Long Guled, a doubtful character dubbed End of Time and three women who dealt with provisions.

On the camels was loaded cotton and canvas sheeting, cow hides to sleep on, Mocha dates, coarse tobacco, biltong, salt, clarified butter, tea, coffee, sugar, water “and a box of biscuits in case of famine”. There were also mosaic earrings, necklaces, watches “and similar nick-nacks” for appeasement.

Burton followed the camels on a white mule with a double-barrelled shotgun across his lap and a brace of Colt six-shooters on his belt.

Thus provisioned, they made their way south across an alluvial plain “here dry, there muddy, [with] warty flats of black mould powdered with nitrous salt”. After a month they entered greener hills with small villages and fields.

Somali raiders attacked them, but fled when fired on, never having encountered a gun. They were stalked by a lion, faced a veld fire, suffered extreme heat and in the mountains nearly froze. “Heat hurts,” End of Time told him, “but cold kills”.

Burton was a keen observer and in place of a yet-to-be invented camera he used his sketchbook and pen to record everything in minute detail over hundreds of pages plus copious footnotes. Today the sophistication of his observations would be called science.

The party overnighted at a village where Burton and End of Time were housed by a beautiful princess, Sudiyah, one of the sheikh’s wives. She served them breakfast of roast beef and mutton with scones drenched in broth.

Burton was charmed by the friendliness of the locals. “In the mining towns of civilised England where the genial brickbat is thrown at the passing stranger, it would have been impossible for me to mingle as I did with these people.”

When Burton fell ill the next day, locals gathered round to watch the stranger “die under a tree far from his fatherland”. But after five days he was better. “A firm resolution (not to die),” he explained in his journal, “sometimes effects its object.”

Leaving the rest of the caravan in the village (they were too terrified to accompany him), three of them left the village with the assurance from the locals that they were dead men. But “cool wind whistled and sunbeams like golden shafts darted through tall, shady trees around whose trunks daisies and blue flowers grew.” They pressed on.

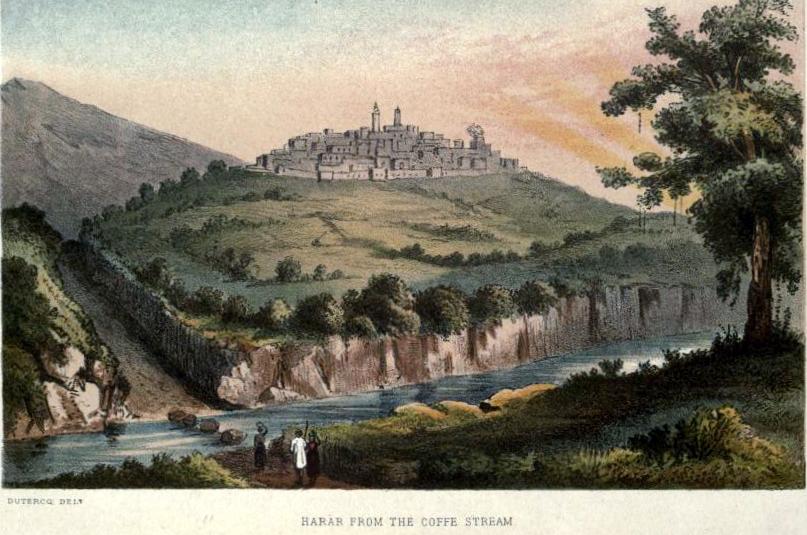

Rounding the northern flank of a mountain and separated by blue valleys, they saw Harar. “Of who have attempted,” Burton mused, “none ever succeeded in entering that pile of stones. The thoroughbred traveller will understand my exultation.” Locals, evidently, didn’t count.

Coming closer, he was less enthusiastic. “The spectacle was a disappointment,” he grumbled. “Many would have grudged exposing three lives to win so paltry a prize.”

Guards at the gate made them wait. There was the sound of clanking chains from a nearby prison. Then they were summoned to meet Ahmad bin Sultan Abubakr. Burton entered the mudbrick palace, made the appropriate greeting and bent to kiss the sultan’s hand.

The man was something of a surprise: an invalid young man of about 25 dressed in flowing robes with a thin beard and a wrinkled brow.

What, he wanted to know, was their errand? Burton had faked a letter from the governor of Aden which he handed over with the governor’s wishes of friendship. The ruse worked. The sultan smiled and dismissed them.

“The Bedouin soldiers in the courtyard were amazed, scarcely believing that the Turk had escaped alive.” Five days later they were on the road bound for the coast.

Burton was under no illusion about the colonial implications of his visit. “I was under the roof of a prince whose least word was death; amongst people who detested foreigners. The only European that had ever passed over their inhospitable threshold – and the fated instrument of their future downfall.” DM/ML

About Us

Australian Saay Harari Association is a non profit, ethnically based, social organization based in Melbourne, Australia.

International Posts

Harar - the Ethiopian city known as 'Africa's Mecca'

Harar unchanged: Inside Ethiopia's timeless city of mosques

Useful Links

Our Contacts

61 Elm Park Dr, Hoppers Crossing

Victoria 3029, Australia

(+614) 018 06 589

(+614) 1364 1816